The Normalcy Fraud

There’s a lie, or at least a spectacular misdirection, that we all learn sometime between middle school math and our first soul-crushing corporate seminar. It’s a beautiful, comforting, and deeply seductive idea. It comes with a lovely picture: a perfect, symmetrical hill, rising gracefully from nothing, peaking in the middle, and falling back to nothing in a gentle, predictable slope.

They call it the Normal Distribution. The Bell Curve.

The name itself is a masterpiece of propaganda.

Normal.

It suggests that this is the default state of the world. It whispers a promise of cosmic fairness. In the Land of Normal, most things are average. Most people are of average height. Most products have average sales. Most days have average weather. Deviations from the average are not only rare, but they become exponentially rarer the further you get from the center. There are no terrifying monsters hiding in the tails. The world, according to this picture, is a safe, cozy, and knowable place.

What a wildly inaccurate map of reality.

It’s a map of a tiny, sheltered bay that we’ve mistaken for the entire storm-tossed ocean. We’ve been trained to spot the gentle curve of the bell, but the real world, the one of money and power and ideas and success, hums to a different, far more violent and lopsided tune. The world is not normal. The world runs on Power Laws. Believing otherwise is the single greatest analytical mistake a person can make, and it’s a mistake we are systematically taught from childhood.

To understand the scale of this delusion, you have to go to a place where the Bell Curve goes to die. A place like Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, California. There, in sleek, minimalist offices you’ll find a tribe of people called venture capitalists.

Let’s invent one. Call him Sal. Sal is sharp, fast-talking, and perpetually caffeinated. He runs a fund with a couple hundred million dollars of other people’s money. His job, in theory, is to invest that money in promising young technology companies. His job, in reality, is to play the lottery.

But Sal has a problem, and it’s not the companies. It’s his investors. Or more precisely, the people who manage his investors’ money. These are the smooth, sober MBA types from the world’s big banks and endowments. They come into his office, armed with thick binders and complex Excel models, and they try to fit Sal’s world into their Bell Curve box.

They’ll say things like, “Sal, we’ve analyzed the mean return of your last twenty investments.” Or, “We need to calculate the standard deviation of your portfolio to assess the risk profile.”

Sal just smiles and orders more coffee. He knows they’re speaking a language from a different planet. One time, a particularly earnest analyst from a Boston pension fund sat across from him and explained, with a series of impeccable charts, that Sal’s strategy was certifiably insane.

“Look at this,” the analyst said, pointing to a graph. “Nine of your last ten investments have returned zero. They’ve gone bankrupt. That’s a 90% failure rate. The tenth one… well, this number is so high it’s breaking our model. It looks like a typo.”

Sal leaned forward. “The ‘typo’,” he said, “is the whole game. It’s the only thing that matters. The other nine? They’re the cost of finding the typo. You’re averaging my tax write offs while I’m hunting for a dragon.”

The analyst didn’t get it. His entire education, his entire professional worldview, was built on the law of averages. In his world, if you have ten investments, you expect a few to do okay, a few to do poorly, and most to land somewhere in the middle. The winners and losers would roughly cancel each other out, and you’d be left with a nice, predictable, average return. His world was the Bell Curve. He was trying to measure a series of rocket launches and explosions with a yardstick.

Sal lives in the real world. A world governed by the Power Curve. In his world, you can invest in ten companies. Nine of them will fail spectacularly, incinerating his money. But the tenth company won’t just do well. It will do so mind-bogglingly, absurdly well that it returns 1,000 times his initial investment. That single winner will pay for all the losers and generate all of the fund’s profits. The average return of his ten investments isn’t just useless as a metric; it’s a dangerous lie. The median return is zero. The mean return is pulled into the stratosphere by a single event.

There is no “middle”.

There is only the grand slam, and the strikeout.

Welcome to the Kingdom of the Outlier, the land where the Power Law reigns.

A Tale of Two Worlds

So what are these two different worlds?

Let’s call them by the names Nassim Taleb, the philosopher-trader who saw this more clearly than anyone, gave them. The world of the Bell Curve is Mediocristan.

The world of the Power Curve is Extremistan.

To understand Mediocristan, imagine you gather 1,000 randomly selected adult men in a large room. You decide to measure their height. The average height will be something like 5 feet 10 inches. Most men will be clustered right around that average. A few will be 6’4”. A few will be 5’6”. It would be exceptionally rare to find someone who is 4’6” or 7’6”.

Now, what happens if you bring the world’s tallest living man into that room? Let’s say he’s 8 feet tall. The average height of the 1,001 men barely budges. It might tick up by a fraction of an inch. The single outlier, even the most extreme one imaginable, has an insignificant effect on the total. In Mediocristan, no single observation can dramatically change the aggregate. This is the world of physical constraints, of many biological phenomena. It is stable and, most importantly, predictable.

The Bell Curve is a fantastic map for this territory.

But that’s not where we live.

Now for Extremistan. Imagine you gather 100 randomly selected people in a bar to measure their net worth. You’d get a few students with debt, some young professionals, a couple of dentists, maybe a small business owner. The average net worth might be, say, $80,000. It’s a meaningful number. You have a decent picture of the room.

Then the door swings open and Jeff Bezos walks in.

Suddenly, the entire picture explodes. The total net worth of the 101 people in the room is now whatever Bezos is worth, let’s say $200 billion, plus the loose change from everyone else. The average net worth is now nearly $2 billion. That number, the “average” tells you absolutely nothing useful about the 100 original people in the room. In fact, it paints a completely false picture of what’s going on. The single outlier isn’t just another data point. The outlier is the story. It’s the only data point that matters.

That’s a Power Law.

Visually, it looks nothing like the gentle Bell. It’s a sheer cliff face followed by a tail that seems to stretch on forever. The peak is ferociously high, representing the one or two winners that dominate everything. Then the graph plummets, and the long, flat tail represents the millions of failures or near-failures.

The critical mistake we’ve made is assuming that the most important parts of modern life unfold in Mediocristan. Our bodies may live there, but our economies, our careers, our technologies, and our cultures all live in Extremistan.

Once you have the glasses to see it, you realize the Power Curve isn’t the exception; it’s the operating system of our world.

We have just been mislabeling it for a century.

Think about book sales. For every J.K. Rowling who sells half a billion books, there are a million authors whose books sell 47 copies, most of them to forgiving relatives. The publishing world isn’t a Bell Curve of moderate successes; it’s a Power Curve of one Harry Potter and a graveyard of forgotten novels.

Think about Hollywood. Disney can release a single Marvel movie that grosses $2.5 billion worldwide. That one film’s profit can cover the losses of a dozen mediocre films and still fund the studio for years. Meanwhile, thousands of independent films are made every year that never even see a theatrical release. The average movie gross is a meaningless number, totally skewed by a handful of superhero blockbusters. It’s a Power Law.

Think about the internet, which is perhaps the greatest Power Law engine ever created. A handful of websites like Google, Facebook, Amazon and X command a colossal share of all human attention. Then there are literally billions of other websites that are, for all practical purposes, invisible. The distribution of YouTube views, TikTok followers, podcast listeners… it’s all the same picture. It’s all the same curve. MrBeast gets more views on a single video than entire genres of content will get in a year.

The stock market? Academics for decades tried to tame it with Bell Curve models, assuming that daily price movements were mostly small and random. They built elegant theories of risk based on standard deviations. Then came days like the crash of 1987, or the financial crisis of 2008, or the flash crashes of the 2010s—single-day events so far out in the “tail” of the Bell Curve they were supposed to be impossible, things that should only happen once every billion years. The market, it turns out, doesn’t live in Mediocristan. A study of the S&P 500 from 1926 to 2016 found that just 4% of stocks accounted for all of the net wealth creation. The other 96% of stocks, in aggregate, delivered a return roughly equal to risk-free Treasury bills.

It’s Sal’s venture capital portfolio, writ large across the entire economy.

The internet didn’t invent the Power Law, but it did pour gasoline on it. In the old world, the friction of physical reality acted as a buffer. A record store only had so much shelf space, forcing it to stock records it thought would have at least average sales, creating an artificial Bell Curve. But on Spotify, with its infinite shelf space, you can see the true Power Law distribution of music: a few dozen global superstars get billions of streams, while millions of artists get a few hundred. Technology stripped away the physical constraints, revealing the brutal, underlying mathematics of Extremistan that was there all along.

So why does this grand misnomer matter?

Who cares if we call the wrong curve “normal”?

It matters because this isn’t just an academic debate. Our devotion to the Bell Curve shapes public policy, corporate strategy, and personal finance, often with disastrous results. It builds a fundamental flaw into our decision-making.

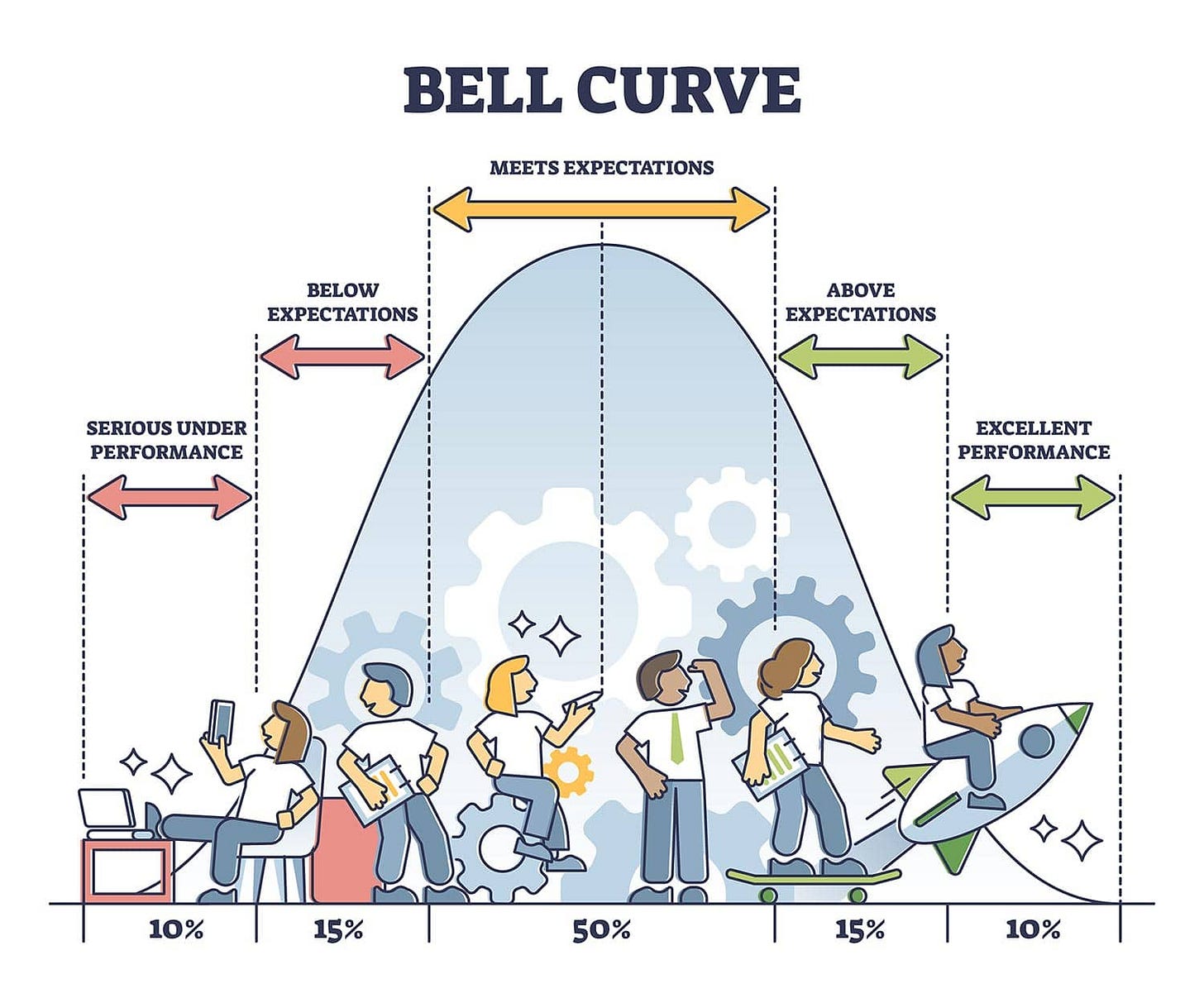

When a corporate HR department insists on force-ranking all its employees on a Bell Curve, mandating that 10% must be “excellent,” 20% “poor,” and 70% “average”, it’s operating under a dangerous delusion. It fails to recognize that in many creative and technical fields, one superstar programmer or engineer might be 100 times more valuable than an average one. By trying to cram a Power Law reality into a Bell Curve box, they end up firing competent people and failing to properly reward the outliers who generate all the value.

When Wall Street banks built their risk models before 2008, they used Bell Curve assumptions to calculate the probability of a nationwide drop in housing prices. They concluded it was essentially impossible. Their models told them they were safe. They lived in Mediocristan. The real world, of course, had other plans. They were standing in a bar with Jeff Bezos and didn’t even know it.

And when we manage our own lives, we are often victims of this same faulty thinking. We are taught to diversify, to seek the average, to avoid failure. But in a Power Law world, where most of the big opportunities in careers and investments lie, the entire game is about finding and riding the outliers. It’s about understanding that most of your bets will probably fail, and that’s okay, as long as one of them has the potential to be a moonshot.

The great irony is that the Bell Curve is, in a way, the distribution of the boring. It describes things that are subject to strong physical or biological limits. But the Power Curve is the distribution of everything else, of anything that can be copied, networked, and scaled: ideas, money, influence, creativity.

To call the Bell Curve “normal” is to suggest that the defining feature of reality is its predictability and its tendency toward the average. But a quick look around tells you that the opposite is true. The world is not driven by the average; it is shaped by the extreme.

The forces that shape our lives are not gentle and symmetrical. They are lopsided, unfair, and wildly unpredictable.

Perhaps it’s time we corrected the record. Let’s call the Bell Curve what it is: the Distribution of the Predictable. The Tame Distribution. And the Power Curve? Let’s call that the Distribution of the Real World. Or maybe, just maybe, let’s start calling that one normal.

Friends: in addition to the 17% discount for becoming annual paid members, we are excited to announce an additional 10% discount when paying with Bitcoin. Reach out to me, these discounts stack on top of each other!

Thank you for helping us accelerate Life in the Singularity by sharing.

I started Life in the Singularity in May 2023 to track all the accelerating changes in AI/ML, robotics, quantum computing and the rest of the technologies accelerating humanity forward into the future. I’m an investor in over a dozen technology companies and I needed a canvas to unfold and examine all the acceleration and breakthroughs across science and technology.

Our brilliant audience includes engineers and executives, incredible technologists, tons of investors, Fortune-500 board members and thousands of people who want to use technology to maximize the utility in their lives.

To help us continue our growth, would you please engage with this post and share us far and wide?! 🙏